Docker and the Device Mapper storage driver

Estimated reading time: 21 minutesDevice Mapper is a kernel-based framework that underpins many advanced

volume management technologies on Linux. Docker’s devicemapper storage driver

leverages the thin provisioning and snapshotting capabilities of this framework

for image and container management. This article refers to the Device Mapper

storage driver as devicemapper, and the kernel framework as Device Mapper.

Note: The Commercially Supported Docker Engine (CS-Engine) running on RHEL and CentOS Linux requires that you use the

devicemapperstorage driver.

An alternative to AUFS

Docker originally ran on Ubuntu and Debian Linux and used AUFS for its storage backend. As Docker became popular, many of the companies that wanted to use it were using Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL). Unfortunately, because the upstream mainline Linux kernel did not include AUFS, RHEL did not use AUFS either.

To correct this Red Hat developers investigated getting AUFS into the mainline

kernel. Ultimately, though, they decided a better idea was to develop a new

storage backend. Moreover, they would base this new storage backend on existing

Device Mapper technology.

Red Hat collaborated with Docker Inc. to contribute this new driver. As a result

of this collaboration, Docker’s Engine was re-engineered to make the storage

backend pluggable. So it was that the devicemapper became the second storage

driver Docker supported.

Device Mapper has been included in the mainline Linux kernel since version

2.6.9. It is a core part of RHEL family of Linux distributions. This means that

the devicemapper storage driver is based on stable code that has a lot of

real-world production deployments and strong community support.

Image layering and sharing

The devicemapper driver stores every image and container on its own virtual

device. These devices are thin-provisioned copy-on-write snapshot devices.

Device Mapper technology works at the block level rather than the file level.

This means that devicemapper storage driver’s thin provisioning and

copy-on-write operations work with blocks rather than entire files.

Note: Snapshots are also referred to as thin devices or virtual devices. They all mean the same thing in the context of the

devicemapperstorage driver.

With devicemapper the high level process for creating images is as follows:

-

The

devicemapperstorage driver creates a thin pool.The pool is created from block devices or loop mounted sparse files (more on this later).

-

Next it creates a base device.

A base device is a thin device with a filesystem. You can see which filesystem is in use by running the

docker infocommand and checking theBacking filesystemvalue. -

Each new image (and image layer) is a snapshot of this base device.

These are thin provisioned copy-on-write snapshots. This means that they are initially empty and only consume space from the pool when data is written to them.

With devicemapper, container layers are snapshots of the image they are

created from. Just as with images, container snapshots are thin provisioned

copy-on-write snapshots. The container snapshot stores all updates to the

container. The devicemapper allocates space to them on-demand from the pool

as and when data is written to the container.

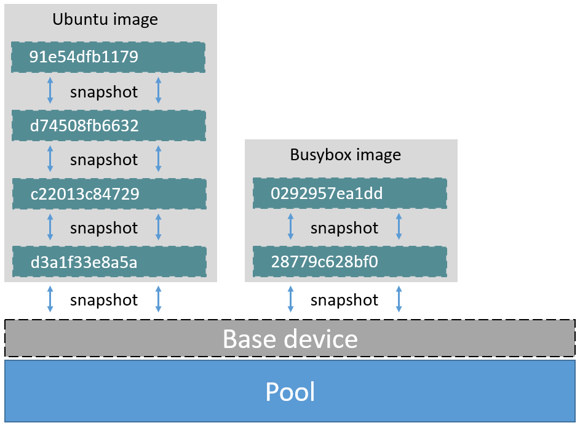

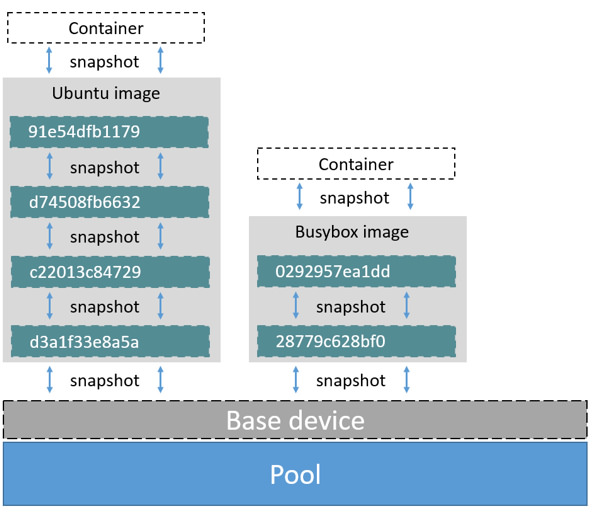

The high level diagram below shows a thin pool with a base device and two images.

If you look closely at the diagram you’ll see that it’s snapshots all the way

down. Each image layer is a snapshot of the layer below it. The lowest layer of

each image is a snapshot of the base device that exists in the pool. This

base device is a Device Mapper artifact and not a Docker image layer.

A container is a snapshot of the image it is created from. The diagram below shows two containers - one based on the Ubuntu image and the other based on the Busybox image.

Reads with the devicemapper

Let’s look at how reads and writes occur using the devicemapper storage

driver. The diagram below shows the high level process for reading a single

block (0x44f) in an example container.

-

An application makes a read request for block

0x44fin the container.Because the container is a thin snapshot of an image it does not have the data. Instead, it has a pointer (PTR) to where the data is stored in the image snapshot lower down in the image stack.

-

The storage driver follows the pointer to block

0xf33in the snapshot relating to image layera005.... -

The

devicemappercopies the contents of block0xf33from the image snapshot to memory in the container. -

The storage driver returns the data to the requesting application.

Write examples

With the devicemapper driver, writing new data to a container is accomplished

by an allocate-on-demand operation. Updating existing data uses a

copy-on-write operation. Because Device Mapper is a block-based technology

these operations occur at the block level.

For example, when making a small change to a large file in a container, the

devicemapper storage driver does not copy the entire file. It only copies the

blocks to be modified. Each block is 64KB.

Writing new data

To write 56KB of new data to a container:

-

An application makes a request to write 56KB of new data to the container.

-

The allocate-on-demand operation allocates a single new 64KB block to the container’s snapshot.

If the write operation is larger than 64KB, multiple new blocks are allocated to the container’s snapshot.

-

The data is written to the newly allocated block.

Overwriting existing data

To modify existing data for the first time:

-

An application makes a request to modify some data in the container.

-

A copy-on-write operation locates the blocks that need updating.

-

The operation allocates new empty blocks to the container snapshot and copies the data into those blocks.

-

The modified data is written into the newly allocated blocks.

The application in the container is unaware of any of these allocate-on-demand and copy-on-write operations. However, they may add latency to the application’s read and write operations.

Configure Docker with devicemapper

The devicemapper is the default Docker storage driver on some Linux

distributions. This includes RHEL and most of its forks. Currently, the

following distributions support the driver:

- RHEL/CentOS/Fedora

- Ubuntu 12.04

- Ubuntu 14.04

- Debian

- Arch Linux

Docker hosts running the devicemapper storage driver default to a

configuration mode known as loop-lvm. This mode uses sparse files to build

the thin pool used by image and container snapshots. The mode is designed to

work out-of-the-box with no additional configuration. However, production

deployments should not run under loop-lvm mode.

You can detect the mode by viewing the docker info command:

$ sudo docker info

Containers: 0

Images: 0

Storage Driver: devicemapper

Pool Name: docker-202:2-25220302-pool

Pool Blocksize: 65.54 kB

Backing Filesystem: xfs

[...]

Data loop file: /var/lib/docker/devicemapper/devicemapper/data

Metadata loop file: /var/lib/docker/devicemapper/devicemapper/metadata

Library Version: 1.02.93-RHEL7 (2015-01-28)

[...]

The output above shows a Docker host running with the devicemapper storage

driver operating in loop-lvm mode. This is indicated by the fact that the

Data loop file and a Metadata loop file are on files under

/var/lib/docker/devicemapper/devicemapper. These are loopback mounted sparse

files.

Configure direct-lvm mode for production

The preferred configuration for production deployments is direct-lvm. This

mode uses block devices to create the thin pool. The following procedure shows

you how to configure a Docker host to use the devicemapper storage driver in

a direct-lvm configuration.

Caution: If you have already run the Docker daemon on your Docker host and have images you want to keep,

pushthem to Docker Hub or your private Docker Trusted Registry before attempting this procedure.

The procedure below will create a logical volume configured as a thin pool to

use as backing for the storage pool. It assumes that you have a spare block

device at /dev/xvdf with enough free space to complete the task. The device

identifier and volume sizes may be different in your environment and you

should substitute your own values throughout the procedure. The procedure also

assumes that the Docker daemon is in the stopped state.

-

Log in to the Docker host you want to configure and stop the Docker daemon.

-

Install the LVM2 and

thin-provisioning-toolspackages.The LVM2 package includes the userspace toolset that provides logical volume management facilities on linux.

The

thin-provisioning-toolspackage allows you to activate and manage your pool. -

Create a physical volume replacing

/dev/xvdfwith your block device.$ pvcreate /dev/xvdf -

Create a ‘docker’ volume group.

$ vgcreate docker /dev/xvdf -

Create a logical volume named

thinpoolandthinpoolmeta.In this example, the data logical is 95% of the ‘docker’ volume group size. Leaving this free space allows for auto expanding of either the data or metadata if space runs low as a temporary stopgap.

$ lvcreate --wipesignatures y -n thinpool docker -l 95%VG $ lvcreate --wipesignatures y -n thinpoolmeta docker -l 1%VG -

Convert the pool to a thin pool.

$ lvconvert -y --zero n -c 512K --thinpool docker/thinpool --poolmetadata docker/thinpoolmeta -

Configure autoextension of thin pools via an

lvmprofile.$ vi /etc/lvm/profile/docker-thinpool.profile -

Specify ‘thin_pool_autoextend_threshold’ value.

The value should be the percentage of space used before

lvmattempts to autoextend the available space (100 = disabled).thin_pool_autoextend_threshold = 80 -

Modify the

thin_pool_autoextend_percentfor when thin pool autoextension occurs.The value’s setting is the perentage of space to increase the thin pool (100 = disabled)

thin_pool_autoextend_percent = 20 -

Check your work, your

docker-thinpool.profilefile should appear similar to the following:An example

/etc/lvm/profile/docker-thinpool.profilefile:activation { thin_pool_autoextend_threshold=80 thin_pool_autoextend_percent=20 } -

Apply your new lvm profile

$ lvchange --metadataprofile docker-thinpool docker/thinpool -

Verify the

lvis monitored.$ lvs -o+seg_monitor -

If the Docker daemon was previously started, move your existing graph driver directory out of the way.

Moving the graph driver removes any images, containers, and volumes in your Docker installation. These commands move the contents of the

/var/lib/dockerdirectory to a new directory named/var/lib/docker.bk. If any of the following steps fail and you need to restore, you can remove/var/lib/dockerand replace it with/var/lib/docker.bk.$ mkdir /var/lib/docker.bk $ mv /var/lib/docker/* /var/lib/docker.bk -

Configure the Docker daemon with specific devicemapper options.

Now that your storage is configured, configure the Docker daemon to use it. There are two ways to do this. You can set options on the command line if you start the daemon there:

--storage-driver=devicemapper \ --storage-opt=dm.thinpooldev=/dev/mapper/docker-thinpool \ --storage-opt=dm.use_deferred_removal=true \ --storage-opt=dm.use_deferred_deletion=trueYou can also set them for startup in the

daemon.jsonconfiguration, for example:{ "storage-driver": "devicemapper", "storage-opts": [ "dm.thinpooldev=/dev/mapper/docker-thinpool", "dm.use_deferred_removal=true", "dm.use_deferred_deletion=true" ] }Note: Always set both

dm.use_deferred_removal=trueanddm.use_deferred_deletion=trueto prevent unintentionally leaking mount points. -

If using systemd and modifying the daemon configuration via unit or drop-in file, reload systemd to scan for changes.

$ systemctl daemon-reload -

Start the Docker daemon.

$ systemctl start docker

After you start the Docker daemon, ensure you monitor your thin pool and volume

group free space. While the volume group will auto-extend, it can still fill

up. To monitor logical volumes, use lvs without options or lvs -a to see tha

data and metadata sizes. To monitor volume group free space, use the vgs command.

Logs can show the auto-extension of the thin pool when it hits the threshold, to view the logs use:

$ journalctl -fu dm-event.service

After you have verified that the configuration is correct, you can remove the

/var/lib/docker.bk directory which contains the previous configuration.

$ rm -rf /var/lib/docker.bk

If you run into repeated problems with thin pool, you can use the

dm.min_free_space option to tune the Engine behavior. This value ensures that

operations fail with a warning when the free space is at or near the minimum.

For information, see the storage driver options in the Engine daemon reference.

Examine devicemapper structures on the host

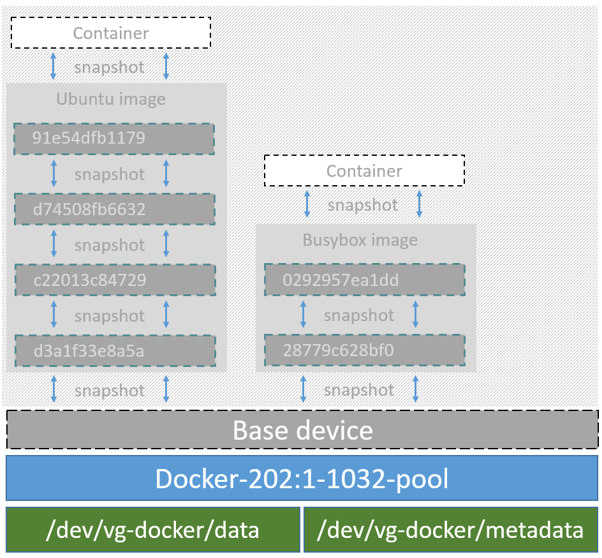

You can use the lsblk command to see the device files created above and the

pool that the devicemapper storage driver creates on top of them.

$ sudo lsblk

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINT

xvda 202:0 0 8G 0 disk

└─xvda1 202:1 0 8G 0 part /

xvdf 202:80 0 10G 0 disk

├─vg--docker-data 253:0 0 90G 0 lvm

│ └─docker-202:1-1032-pool 253:2 0 10G 0 dm

└─vg--docker-metadata 253:1 0 4G 0 lvm

└─docker-202:1-1032-pool 253:2 0 10G 0 dm

The diagram below shows the image from prior examples updated with the detail

from the lsblk command above.

In the diagram, the pool is named Docker-202:1-1032-pool and spans the data

and metadata devices created earlier. The devicemapper constructs the pool

name as follows:

Docker-MAJ:MIN-INO-pool

MAJ, MIN and INO refer to the major and minor device numbers and inode.

Because Device Mapper operates at the block level it is more difficult to see

diffs between image layers and containers. Docker 1.10 and later no longer

matches image layer IDs with directory names in /var/lib/docker. However,

there are two key directories. The /var/lib/docker/devicemapper/mnt directory

contains the mount points for image and container layers. The

/var/lib/docker/devicemapper/metadatadirectory contains one file for every

image layer and container snapshot. The files contain metadata about each

snapshot in JSON format.

Increase capacity on a running device

You can increase the capacity of the pool on a running thin-pool device. This is useful if the data’s logical volume is full and the volume group is at full capacity.

For a loop-lvm configuration

In this scenario, the thin pool is configured to use loop-lvm mode. To show

the specifics of the existing configuration use docker info:

$ sudo docker info

Containers: 0

Running: 0

Paused: 0

Stopped: 0

Images: 2

Server Version: 1.11.0

Storage Driver: devicemapper

Pool Name: docker-8:1-123141-pool

Pool Blocksize: 65.54 kB

Base Device Size: 10.74 GB

Backing Filesystem: ext4

Data file: /dev/loop0

Metadata file: /dev/loop1

Data Space Used: 1.202 GB

Data Space Total: 107.4 GB

Data Space Available: 4.506 GB

Metadata Space Used: 1.729 MB

Metadata Space Total: 2.147 GB

Metadata Space Available: 2.146 GB

Udev Sync Supported: true

Deferred Removal Enabled: false

Deferred Deletion Enabled: false

Deferred Deleted Device Count: 0

Data loop file: /var/lib/docker/devicemapper/devicemapper/data

WARNING: Usage of loopback devices is strongly discouraged for production use. Use `--storage-opt dm.thinpooldev` to specify a custom block storage device.

Metadata loop file: /var/lib/docker/devicemapper/devicemapper/metadata

Library Version: 1.02.90 (2014-09-01)

Logging Driver: json-file

[...]

The Data Space values show that the pool is 100GB total. This example extends the pool to 200GB.

-

List the sizes of the devices.

$ sudo ls -lh /var/lib/docker/devicemapper/devicemapper/ total 1175492 -rw------- 1 root root 100G Mar 30 05:22 data -rw------- 1 root root 2.0G Mar 31 11:17 metadata -

Truncate

datafile to the size of themetadatafile (approximately 200GB).$ sudo truncate -s 214748364800 /var/lib/docker/devicemapper/devicemapper/data -

Verify the file size changed.

$ sudo ls -lh /var/lib/docker/devicemapper/devicemapper/ total 1.2G -rw------- 1 root root 200G Apr 14 08:47 data -rw------- 1 root root 2.0G Apr 19 13:27 metadata -

Reload data loop device

$ sudo blockdev --getsize64 /dev/loop0 107374182400 $ sudo losetup -c /dev/loop0 $ sudo blockdev --getsize64 /dev/loop0 214748364800 -

Reload devicemapper thin pool.

a. Get the pool name first.

```bash $ sudo dmsetup status | grep pool docker-8:1-123141-pool: 0 209715200 thin-pool 91 422/524288 18338/1638400 - rw discard_passdown queue_if_no_space - ``` The name is the string before the colon.b. Dump the device mapper table first.

```bash $ sudo dmsetup table docker-8:1-123141-pool 0 209715200 thin-pool 7:1 7:0 128 32768 1 skip_block_zeroing ```c. Calculate the real total sectors of the thin pool now.

Change the second number of the table info (i.e. the disk end sector) to reflect the new number of 512 byte sectors in the disk. For example, as the new loop size is 200GB, change the second number to 419430400.d. Reload the thin pool with the new sector number

```bash $ sudo dmsetup suspend docker-8:1-123141-pool \ && sudo dmsetup reload docker-8:1-123141-pool --table '0 419430400 thin-pool 7:1 7:0 128 32768 1 skip_block_zeroing' \ && sudo dmsetup resume docker-8:1-123141-pool ```

The device_tool

The Docker’s projects contrib directory contains not part of the core

distribution. These tools that are often useful but can also be out-of-date. In this directory, is the device_tool.go

which you can also resize the loop-lvm thin pool.

To use the tool, compile it first. Then, do the following to resize the pool:

$ ./device_tool resize 200GB

For a direct-lvm mode configuration

In this example, you extend the capacity of a running device that uses the

direct-lvm configuration. This example assumes you are using the /dev/sdh1

disk partition.

-

Extend the volume group (VG)

vg-docker.$ sudo vgextend vg-docker /dev/sdh1 Volume group "vg-docker" successfully extendedYour volume group may use a different name.

-

Extend the

datalogical volume(LV)vg-docker/data$ sudo lvextend -l+100%FREE -n vg-docker/data Extending logical volume data to 200 GiB Logical volume data successfully resized -

Reload devicemapper thin pool.

a. Get the pool name.

```bash $ sudo dmsetup status | grep pool docker-253:17-1835016-pool: 0 96460800 thin-pool 51593 6270/1048576 701943/753600 - rw no_discard_passdown queue_if_no_space ``` The name is the string before the colon.b. Dump the device mapper table.

```bash $ sudo dmsetup table docker-253:17-1835016-pool 0 96460800 thin-pool 252:0 252:1 128 32768 1 skip_block_zeroing ```c. Calculate the real total sectors of the thin pool now. we can use

blockdevto get the real size of data lv.Change the second number of the table info (i.e. the number of sectors) to reflect the new number of 512 byte sectors in the disk. For example, as the new data `lv` size is `264132100096` bytes, change the second number to `515883008`. ```bash $ sudo blockdev --getsize64 /dev/vg-docker/data 264132100096 ```d. Then reload the thin pool with the new sector number.

```bash $ sudo dmsetup suspend docker-253:17-1835016-pool \ && sudo dmsetup reload docker-253:17-1835016-pool --table '0 515883008 thin-pool 252:0 252:1 128 32768 1 skip_block_zeroing' \ && sudo dmsetup resume docker-253:17-1835016-pool ```

Device Mapper and Docker performance

It is important to understand the impact that allocate-on-demand and copy-on-write operations can have on overall container performance.

Allocate-on-demand performance impact

The devicemapper storage driver allocates new blocks to a container via an

allocate-on-demand operation. This means that each time an app writes to

somewhere new inside a container, one or more empty blocks has to be located

from the pool and mapped into the container.

All blocks are 64KB. A write that uses less than 64KB still results in a single 64KB block being allocated. Writing more than 64KB of data uses multiple 64KB blocks. This can impact container performance, especially in containers that perform lots of small writes. However, once a block is allocated to a container subsequent reads and writes can operate directly on that block.

Copy-on-write performance impact

Each time a container updates existing data for the first time, the

devicemapper storage driver has to perform a copy-on-write operation. This

copies the data from the image snapshot to the container’s snapshot. This

process can have a noticeable impact on container performance.

All copy-on-write operations have a 64KB granularity. As a results, updating 32KB of a 1GB file causes the driver to copy a single 64KB block into the container’s snapshot. This has obvious performance advantages over file-level copy-on-write operations which would require copying the entire 1GB file into the container layer.

In practice, however, containers that perform lots of small block writes

(<64KB) can perform worse with devicemapper than with AUFS.

Other device mapper performance considerations

There are several other things that impact the performance of the

devicemapper storage driver.

-

The mode. The default mode for Docker running the

devicemapperstorage driver isloop-lvm. This mode uses sparse files and suffers from poor performance. It is not recommended for production. The recommended mode for production environments isdirect-lvmwhere the storage driver writes directly to raw block devices. -

High speed storage. For best performance you should place the

Data fileandMetadata fileon high speed storage such as SSD. This can be direct attached storage or from a SAN or NAS array. -

Memory usage.

devicemapperis not the most memory efficient Docker storage driver. Launching n copies of the same container loads n copies of its files into memory. This can have a memory impact on your Docker host. As a result, thedevicemapperstorage driver may not be the best choice for PaaS and other high density use cases.

One final point, data volumes provide the best and most predictable performance. This is because they bypass the storage driver and do not incur any of the potential overheads introduced by thin provisioning and copy-on-write. For this reason, you should to place heavy write workloads on data volumes.

Related Information

- Understand images, containers, and storage drivers

- Select a storage driver

- AUFS storage driver in practice

- Btrfs storage driver in practice

- daemon reference

Feedback? Suggestions? Can't find something in the docs?

Feedback? Suggestions? Can't find something in the docs?Edit this page ● Request docs changes ● Get support

Rate this page: